Creating an API can entail having to make synchronous tasks available, i.e. where the caller actively waits for a response before processing can continue.

Asynchronous tasks (fire-and-forget, or making use of a call-back mechanism) are admittedly often presented as the panacea for such situations. But let’s put that aside and concentrate on synchronous tasks, starting from the basis that the need for such tasks is justified – which can be perfectly true!

As integration specialists, we advocate decoupling as basic best practice, taking three forms:

This should, in theory, enable us to introduce maximum flexibility and adaptability in the integration layer, and thereby pull off the trick of fitting a square peg into a round hole. These are the decoupling principles found in Messaging patterns.

Yes, but bear in mind:

At first glance, these “constraints” seem incompatible with the requirements of an API, which demands acceptable response times. This is also the kind of scenario under which pragmatism is a tempting option, whereby close enough is good enough, perfect is the enemy of good, etc. Thoughts that, although necessary when applying scientific doubt, are too often the precursors to the deliberate introduction of technical debt (for further reading, see Mark Heath’s excellent article: Top 7 Reasons For Introducing Technical Debt) for reasons that are sometimes simply a matter of preconceptions.

But is perfect really the enemy of good? Is the best practice of decoupling, as mentioned above, incompatible with, or inapplicable to, synchronous APIs? Put another way: are we always forced to choose between synchronous and asynchronous?

To establish these ideas, let’s take the practical example of a customer management API exposing a customer creation task. This transaction has to:

Within the Azure ecosystem, messaging scenarios can be addressed by more than one component, the main ones being:

<li>EventGrid

Each has its specific features and favored use cases. Microsoft’s documentation on the subject is fairly clear, so you are advised to read it if you have not already done so.

Returning to the two customer management API responsibilities described above:

Therefore, Service Bus is my choice as the backbone for this API. The technical architecture is very simple:

functions subscribing to events and publishing responses.

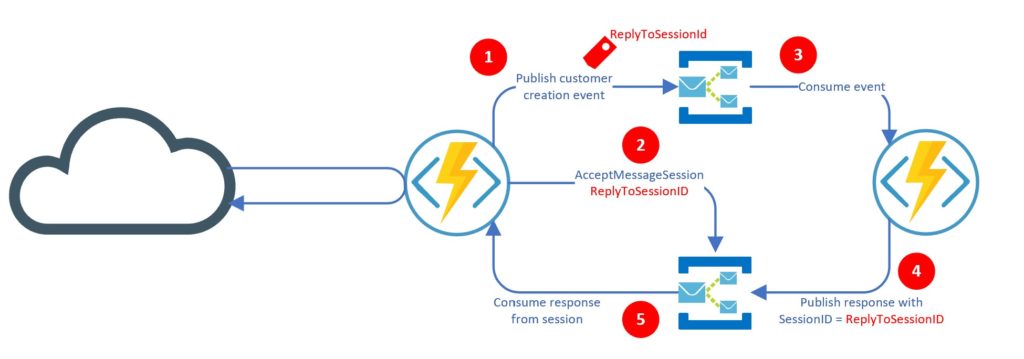

The overview diagram is shown below:

It works as follows:

An example of the code follows:

Message requestMessage = new Message(System.Text.Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(requestBody));

requestMessage.ReplyTo = responseEntity;

requestMessage.ReplyToSessionId = requestID;

requestMessage.SessionId = requestID;

requestMessage.UserProperties.Add("EventType", "CreationRequested");

requestMessage.UserProperties.Add("CountryCode", "FRA");

IMessageSession session = await rcvClient.AcceptMessageSessionAsync(requestID); Message response = await session.ReceiveAsync(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(responseTimeout));

outputMessage.SessionId = inputMessage.ReplyToSessionId;

And that is all there is to it! The scenario can obviously be expanded to include a sequence of events and further processing, but the basic principle remains as described above.

It all looks good on paper, but what about actual performances? Response time is a key issue for an API. The latency caused by decoupling using the Service Bus must therefore remain acceptable and under control, because it can vary both over time and with the workload.

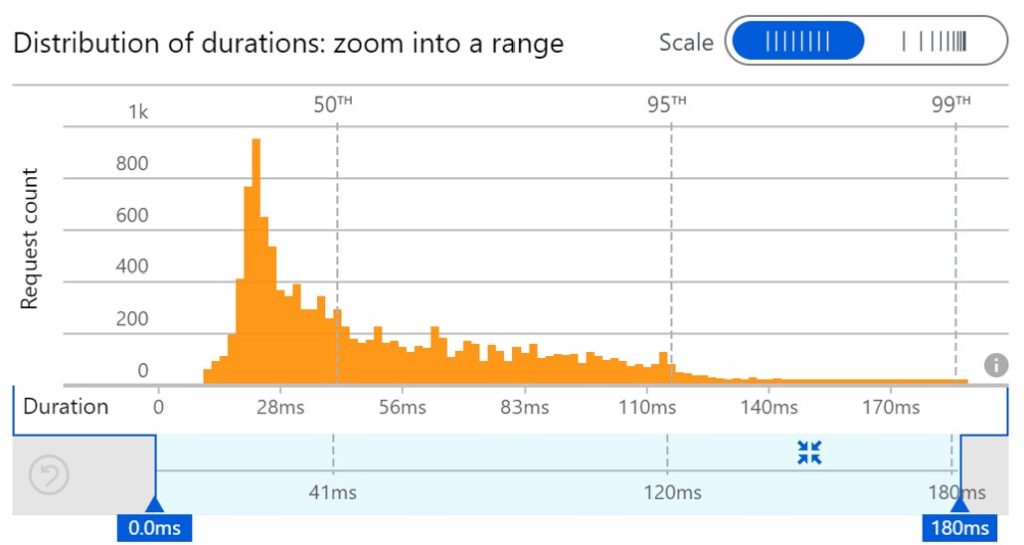

I have run a number of performance tests based on a simple Service Bus Standard namespace. My API does not need to exceed 50 requests per second, so I took a few precautions, and multiplied this workload by 10, and tested how it worked with 500 requests per second. The results are shown below:

These results show very consistent levels of performance with a fairly narrow distribution, and latency very much under control not exceeding 200 ms. The tests I was able to run on Premium show no gains as regards these aspects but, in my case, the performance obtained is entirely satisfactory anyway.

NOTE: one might conclude that as Premium delivers no performance benefits, a Standard namespace will suffice. But bear in mind that Standard is not designed for performance. It is intended only to supply Messaging as a Service functionalities. Indeed, it uses shared infrastructure, so the risk of “noisy neighbors” is real, although Microsoft is currently working on putting in place performance smoothing mechanisms (which will certainly entail some form of throttling). In other words, there is no guarantee that the performances described above will be maintained over the long term. Service Bus Premium, meanwhile, is built for performance, including by making use of radically different infrastructure.

My intention here is not to state an absolute rule: it is advisable for readers to learn about these factors and examine how they fit with their requirements. Nevertheless, my personal conclusions are:

And on that point, I wish you happy messaging! 🙂