In the world of computing, programming languages are essential tools used to communicate complex operations to a computer. Their main purpose is to provide a language understandable by humans, which is then transformed into something closer to machine code when it comes to compiled languages.

In this effort to offer a more human-friendly interface, the vocabulary of programming languages evolves to become more readable and concise. Syntactic sugar refers to language features that simplify a developer’s daily work.

In this article, we’ll explore three syntactic sugars in one of the languages that embraces them the most: C#.

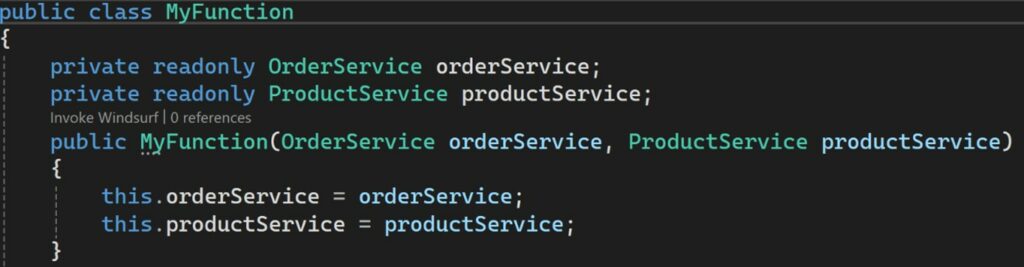

In C#, constructors are used to specify which fields are needed to create an object.

Often, this means initializing fields — a repetitive task when the parameter names and field names are the same.

The primary constructor was introduced to simplify this tedious job.

(It’s not a constructor that brings you back to childhood, but one that simplifies your life!)

It allows constructor parameters to be available across the whole class.

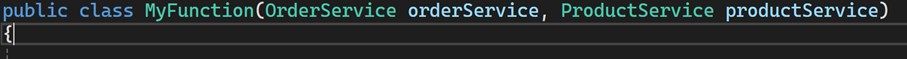

To define it, just add the parameters after the class definition:

Without a primary constructor:

With a primary constructor:

Important: Fields from the primary constructor are not public properties by default.

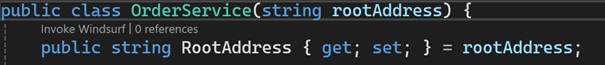

You can’t do this.param. If needed, you can assign them to properties like this:

C# provides a data structure meant to represent… data.

To define it, just replace the word class with record:

public record Foo{}

Why not just use a class? Let’s take a look at what records offer on top of that.

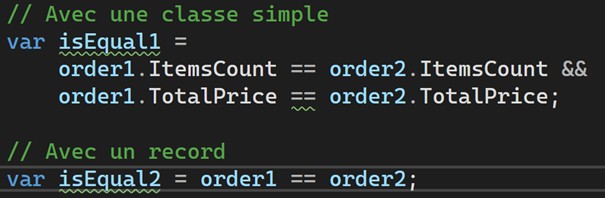

If you want to compare two class instances based on their properties, you’d need to manually compare each one.

This is because, with classes, the = operator compares references.

With a record, however, you can directly compare two instances.

The = operator compares the values of the properties.

For example, for a class Order with ItemsCount and TotalPrice fields:

With a record, duplication is super simple!

Just use with {} after a record instance — you can even override values inside the brackets:

![]()

As seen in section 1, in classes, fields from the primary constructor do not become public properties.

But with records, they do!

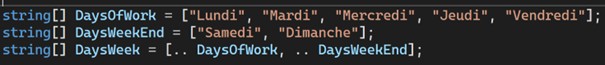

You can define a collection simply using curly braces with comma-separated elements.

You can also concatenate multiple collections using the .. operator, which “spreads” a collection into another:

You can retrieve a portion of an indexed collection by specifying a start and end index using the following syntax: collection[start..end].

Bonus: To define the end index relative to the end of the collection, prefix the index with ^.

For example, [..^2] returns all elements except the last two.